The previous post gave an overview of the different "tiger and treasure" logic puzzles that could be formed from a starting list of 14 statements:

- this room has treasure

- the other room has treasure

- at least one room has treasure

- both rooms have treasure

- this room has a tiger

- the other room has a tiger

- at least one room has a tiger

- both rooms have a tiger

- this room has treasure or the other room has a tiger

- the other room has treasure or this room has a tiger

- this room has treasure and the other room has a tiger

- the other room has treasure and this room has a tiger

- both rooms have treasure or both rooms have a tiger

- one room has treasure and the other has a tiger

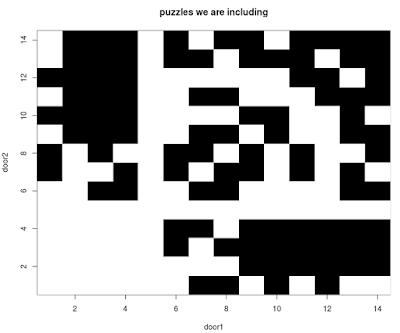

When exploring all the different possible puzzles we can make from these, we won't include puzzles that lead to a contradiction, or puzzles where the clues don't allow you to identify either door. This leaves 96 good puzzles out of the 196 combinations of statements, shown in black below:

Symmetry among Puzzles

For each statement in the list of fourteen, you can find the negation of that statement in the list - for example, statement 1 "this room has treasure" has its negation in statement 5 "this room has a tiger." If we plot the list of statements on door 1 vs. the the list of statements on door 2, but re-arrange the statements on the door 2 axis so they are the negations of our original list (the negated list would be statements 5, 6, 8, 7, 1 ,2, 4, 3, 12, 11, 10, 9, 14, 13), we can see the symmetry in these puzzles more clearly:This graph is telling us that if we have a puzzle that works, then if we swap the signs on the doors and negate them, we will also get a working puzzle. If you explore this a bit further, you'll see that the symmetry goes deeper. Let's get a little mathy with this.

If a and b are statements in our list, a puzzle P can be described by the ordered pair (a,b). Every puzzle P also has a solution, (s, t) where s and t are either "tiger", "treasure", or "unknown."

For any statement in the list x, we can write the negation of x as -x. If we form a new puzzle by putting the negation of a on door 2 and the negation of b on door 1, we get a new puzzle -P = (-b,-a).

The symmetry of our tiger treasure puzzles can be expressed as this little theorem:

If P = (a,b) is a tiger treasure puzzle with solution (s,t), then its negation, -P = (-b, -a), will have the solution (t, s).Here is an example. Consider the example puzzle from the previous post.

Puzzle P

Door 1 says: Both rooms have a tiger. (statement 8)

Door 2 says: The other room has treasure and this room has a tiger. (statement 12)

In the previous post, we worked out that door 1 has a tiger and door 2 has treasure.

Statement 8's negation is statement 3, and statement 12's negation is statement 9. So the puzzle -P looks like this:

Puzzle -P

Door 1 says: This room has treasure or the other room has a tiger (statement 9)

Door 2 says: At least one room has treasure (statement 3)

If you have tried out a few of these, you may be able to find the solution to -P, which is that door 1 has a tiger and door 2 has treasure, which is the reverse of Puzzle P, where door 1 had treasure and door 2 had the tiger - the contents behind the doors have switched.

The symmetric graph above helped point us towards a nice symmetry that holds true for all of the tiger and treasure puzzles, but our original non-symmetric graph can point to another interesting things too.

Using asymmetry to make puzzles more interesting

In Raymond Smullyan's book "The Lady or the Tiger?" he presented a nice twist on the usual presentation of this kind of puzzle:

"There are no signs above the doors!" exclaimed the prisoner. "Quite true," said the king. "The signs were just made, and I haven't had time to put them up yet." "Then how do you expect me to choose?" demanded the prisoner. "Well, here are the signs," replied the king. That's all well and good," said the prisoner anxiously, "but which sign goes on which door?" The king thought awhile. "I needn't tell you," he said. "You can solve this problem without that information."

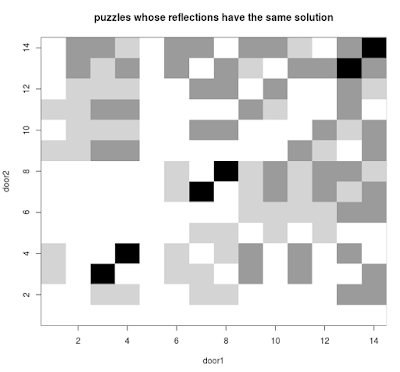

Let's look around for puzzles like this. One question to ask: Which of our problems would allow us to interchange the signs on the doors without affecting the solution to the problem? We'd like to know when does P = (a,b) give the same solution as Q = (b,a)? To explore which puzzles might work in this way, we can start looking at our first graph above, but limit our attention to those puzzles who's reflection in the line door1= door2 is also a puzzle. These are shown in black below (grey shows other puzzles whose reflection is not also a puzzle).

But we don't just want puzzles whose reflection gives us a puzzle, but ones whose reflections have the same solution as the original. It turns out that this gives an uninspiring set of six puzzles:

Only the trivial cases work: puzzles where the statements on the doors are exactly the same end up giving us puzzles that have exactly the same solution when the statements are interchanged. So what about the problem from "The Lady or the Tiger?", it uses these statements:

- this room contains a tiger (statement 5)

- both rooms contain tigers (statement 8)

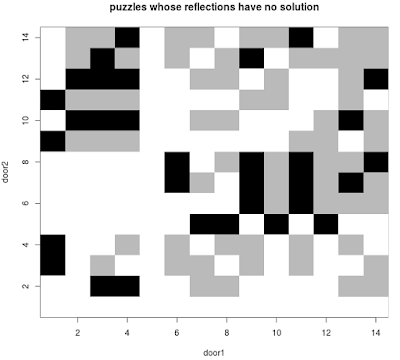

Why does the solver not need to know which door each goes on? Well, if statement 5 goes on door 1 we get a contradiction, so it must go on door 2. This is why the solver does not need to be told how to label the doors: there is only one possible way to do so without getting a contradiction. So, a way to find more problems like this is to look for puzzles P = (a,b) where P is a legitimate puzzle, but Q = (b, a) is not a puzzle, as that labelling of the doors leads to a contradiction.

For example, the puzzle (13, 10) falls into this set.

Let's try putting 13 on door 1 and 10 on door 2:

door 1: both rooms have treasure or both rooms have a tiger (13)

door 2: the other room has treasure or this room has a tiger (10)

Because inscriptions on door 1 are only true of door 1 leads to treasure, statement 13 implies that door 2 must lead to treasure. Door 2 leading to treasure makes its statement (10) false, requiring door 1 to lead to a tiger.

However, if we switch the statements, we run into trouble:

door 1: the other room has treasure or this room has a tiger (10)

If statement 10 on door 1 is false, then door 1 would lead to a tiger. However, the statement says that it leads to a tiger, so this cannot be. Door 1 must lead to treasure, making statement 10 true, requiring door 2 to also lead to a treasure. If door 2 leads to treasure, then its statement (13) must be false. However, statement 13 is true (both rooms have treasure), a contradiction.

So, presented with statements 10 and 13, there is only one way to arrange them on the doors: put statement 13 on door 1 and statement 10 on door 2, leading to a tiger behind door 1 and treasure behind door 2.

Please try out the tiger-treasure puzzles here and ask yourself: "What would the negation of this puzzle (-P) be?" and "Is this one of the 38 puzzles that can be answered without being told which sign is on which door?"